By Michael A. Velez, Managing Director of Castellan Systems

Let me start by giving a little background of myself. I’ve been in IT for over 40 years; I cut my first line of code in January 1978! All I wanted back then was to write computer software but at that time there was no natural progression path, at least where I worked, that allowed me to progress in seniority while remaining in a technical role. The more experienced I became the more management duties I was allocated. First as a technical team leader and eventually to project manager, portfolio manager and programme manager. In the end, I ended in Project/Portfolio/Programme Management for 2 thirds of my professional life so far. In that time, I have worked in over 100 projects and I’ve performed the project, programme and portfolio manager roles. So, I believe I’m well placed to look and clarify a few things.

At my last engagement working for someone else, before I decided to concentrate all my professional energies on Castellan Systems, I was confronted by how little people knew about the difference between programmes and portfolios in relation to managing projects. What made this even more astonishing was that highly qualified people within the project management field were part of this misinformed group.

The organisation was a financial services company owned by a state government in Australia. The Project Management Office (PMO) Manager and new CEO imposed by this state government were members of this uninformed group. I was hired as a programme/project manager; I was to manage 2 programmes and their projects. But once I started and was handed over these 2 “programmes” it became very obvious that they weren’t programmes at all. One was a group of projects, each for a different client of the company, to produce annual statements for all their members. While they seemed similar, generate annual statements, that was the only characteristic they had in common. Each had a different client; if one was not delivered, it didn’t impact any of the others; each required resources from different business and IT teams. Cancelling one didn’t impact any of the others in any way. The other “programme” was a collection of projects for a specific client. Their only relationship was the client and the fact that they had been identified by that client in that financial year. Once we completed some of them, we started new ones. The picture was the same for the other clients; programmes where portfolios should had been in place.

So, after a succession of PMO managers, we finally got one that seemed to understand this difference but their “engagement” didn’t last too long. Soon the original PMO manager came back as a consultant to assist with a major restructuring of the whole business only to reimposed the misguided structure and the CEO agreed with this person; he even confirmed this to the whole of the PMO team, PMs and BAs, at a meeting we requested with him. So, the portfolio managers and pool of project managers were replaced by a group of programme managers to run “programmes”, which were actually portfolios, and their projects. The one programme the organisation actually had at the time was called a project!

It was at this point that I said I had enough; I left the organisation and swore never to work for another such organisation again. I’m now happily running my own company the way I think it should be done based on the knowledge acquired through training and work over more years than I care to mention.

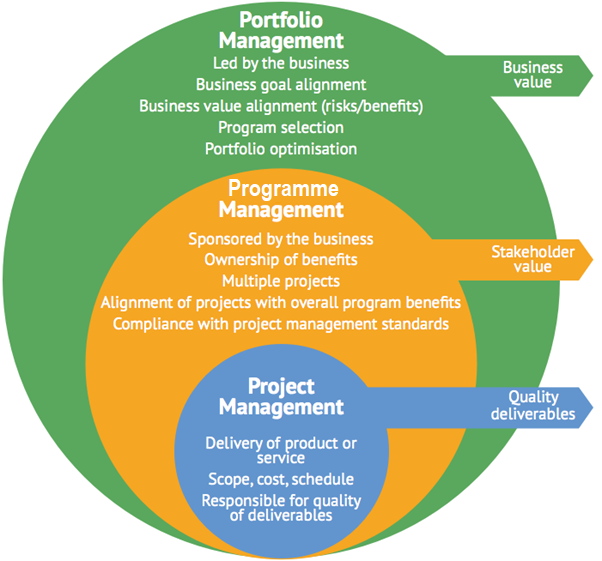

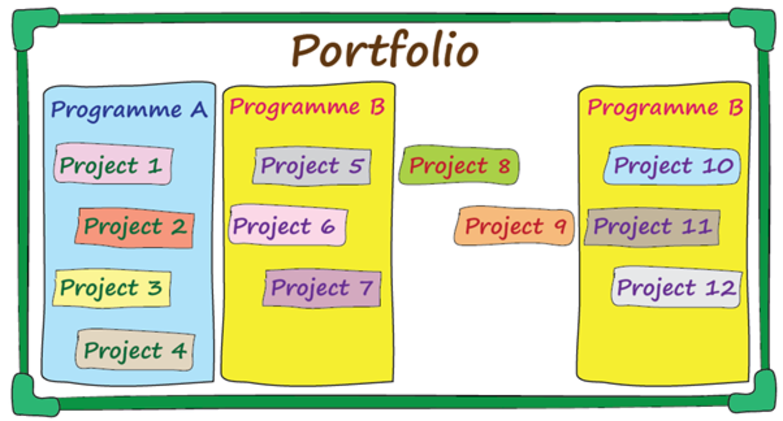

So, let’s begin; the diagram below shows the relationship between portfolios, programmes and projects. I think it’s fairly clear but let’s look closer into this subject.

What is a programme?

|

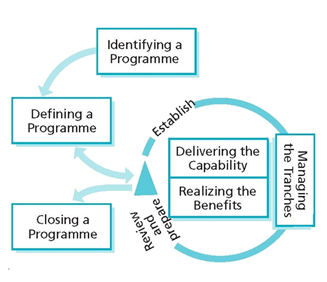

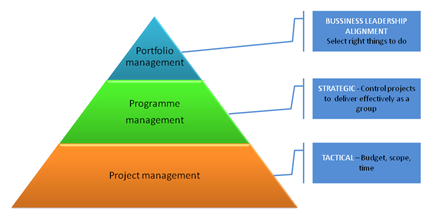

The ultimate goal of a Programme is to realise outcomes and benefits of strategic relevance. To achieve this a programme is designed as a temporary flexible organisation structure created to coordinate, direct and oversee the implementation of a set of related projects and activities in order to deliver outcomes and benefits related to the organisation's strategic objectives. A programme is likely to have a life that spans several years. A Project is usually of shorter duration (a few months perhaps) and will be focussed on the creation of a set of deliverables within agreed cost, time and quality parameters. Programmes usually require the commitment and active involvement of more than one organisation to achieve the desired outcomes. Programmes deliver, or enable, one or more benefits i.e. measurable improvement resulting from an outcome and perceived as an advantage by one or more stakeholders. |

|

What is a portfolio?

|

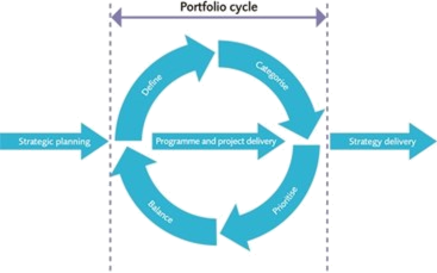

The term Portfolio is used to describe the total set of programmes and stand-alone projects undertaken by an organisation. It can also include other project related activities and responsibilities. The purpose of a portfolio is to establish centralised management and oversight for many projects and/or programmes. A portfolio also helps establish standardised governance across the organisation. The purpose of creating and managing a portfolio is to ensure the business is taking on the right projects, and making sure they align with the company’s values, strategies, and goals. |

How does a portfolio relate to programmes and projects?

Programmes are created to group together similar or related projects. This allows for strategic management of interdependencies, such as shared resources. Portfolios are created to ensure projects and programmes align with the strategy of the business. Let’s say your company builds and repairs ships. The construction of a naval ship would be a project. The repairs of a commercial ferry would be another project. These two projects are unlikely to be grouped together into a programme because they’re not very similar. If there were five separate projects to construct five separate naval ships, they would likely have many factors in common, such as:

- Similar scopes;

- Common requirements;

- The same resource demands;

- Shared stakeholders;

- Identical quality measures;

- Similar timelines;

- And so on.

|

Therefore, management may decide it’s best to group them together as a programme, under a programme manager. This could allow for opportunities, such as discounts for ordering five ships worth of material together. It could also assist with sharing resources, knowledge, best practices, and other assets across projects. Now consider that your shipyard can only take on so much work at a time. For instance, you may only be able to take on five projects at a time, regardless of the type of job (repair or build). Although commercial repairs and naval construction are not in the same program, they may become part of the same portfolio, if it makes sense for the business. Portfolio management would help ensure the company balances the overall number and type of projects it takes on. In this case, it would ensure the total projects planned at one time does not exceed its maximum capacity of five. It can also help ensure the company takes on the appropriate project ratio. For example, repair projects are likely to be shorter-term, higher risk, but more profitable. While construction projects will be longer-term, lower-risk, but less profitable. Depending on the company’s priorities and appetite for risk, management may want to maximise one type of project over the other. But if they’re not managed under a centralised portfolio, this type of strategic planning would be difficult, if not impossible. |

|

Portfolio managers look at a company’s projects and evaluate whether they're are being executed well, how they could be improved, and whether the organisation is experiencing the expected benefits.

Let’s put it in simple terms

A programme can be looked at a really large project. Just like a project it has a beginning and an end; it has a scope, business goals & objectives and required set of deliverables. The projects within the programme are inter-related; it is the total delivery of these projects that delivers on the outcomes and benefits of the programme. Failure to deliver on just a single of these projects could lead to a failure in achieving these outcomes and benefits.

A portfolio is just a group of projects with little or no relationship between them. The only link could be the capacity of the organisation to deliver projects within a defined period (for internal projects) or the business area or client who owns the projects.

So, if I take it back to my engagement that I mentioned in my introduction, a programme would be all projects relating to some major business transformation or to deliver on some major new government legislation affecting the operation of the industry which the organisation is involved. But a programme is not all of the projects the organisation undertakes for a client over the life of the contract with that aforementioned client. If you fail to deliver any project within the portfolio, only the outcomes and benefits of that project will not be delivered without impacting the other projects’ chance of delivering theirs. If there is a chance of failure to deliver on a project impacts another, that’s because those projects are actually a programme within the portfolio.

Remember that a programme, like a project, is a temporary undertaking with a beginning and an end and a set of objectives, outcomes and benefits. A portfolio, especially in the case of a client’s portfolio, begins when the contract with the client is signed and normally only ends if and when that contract is terminated by either party.

When you start a programme, you know what you’re trying to achieve; when you start a portfolio you don’t, from a outcomes and benefits point of view. They serve difference purposes; a programme can be view as a really big project with many facets.

A portfolio can be view as a way of coordinating the available budget and capacity of the organisation to execute projects for their own internal business or for a contracted client. The establishment of a portfolio is more for the management of the processes, methods, and technologies used by project managers and project management offices (PMOs) to analyse and collectively manage current or proposed projects based on numerous key characteristics.

Does it make much of a difference?

Well yes it does on many different levels. Let’s explore them.

A programme’s budget and business case are usually established as a whole. It’s the whole programme that makes sense and not each individual project. In a portfolio, the budget and business case are established individually per project. Just because the business case of one project doesn’t stand-up to scrutiny, it doesn’t really impact the business case of another. The portfolio in itself usually has no budget, other that the “bucket” of funding available for projects in a period of time, usually a financial year.

While there is an overlap of skills that programme managers and portfolio managers share, there are also a set of unique skills that each discipline requires. Pipeline (or demand or queue) management is an important process in Portfolio Management but not really in Programme Management. Pipeline management involves steps to ensure that an adequate number of project proposals are generated and evaluated to determine whether (and how) a set of projects in the portfolio can be executed with finite development resources in a specified time. In a programme, the projects are generated out of the evaluation and clarification of the vision and business case. While both need to be great communicators, a portfolio manager also needs to be a salesman. I have seen salesmen and client relationship managers (CRMs) be effective portfolio managers and I have seen portfolio managers be effective salesmen and even CRMs. But salesmen and CRMs can’t really be programme managers, they lack those project management skills; programme managers usually are highly experienced project managers. Also, while a programme manager may have need to be a bit of a salesman, they just can’t really function as an out and out salesman or CRM.

A portfolio manager needs to maintain a very close relationship with their client’s entire organisation (may be through some central project approval board) in order to know what projects the client has in the pipeline and their priority so that they can begin planning for them, especially when it comes to resourcing. That’s why resource management is so critical to portfolio management. While a programme manager also needs to maintain a close relationship to their client, this is more to the client involved in the programme and not the entire organisation, like the portfolio manager.

So, maybe I need to give you a couple of examples. I worked for 27 out of those 40 odd years I mentioned above supporting a steelworks in Australia. For the first 9 years employed directly by the steelworks, the following 10 for an IT company fully owned by the steelworks parent company and the final 8 years for an IT services company to which the IT operation had been outsourced. The steelworks’ operations cover from the moment the raw materials arrive from the mines to the delivery of various shaped products to down process industries. Their products have been used in shipbuilding, pipe building, the car and whitegoods industry and construction industry. Many ships and all of the current submarines in the Royal Australian Navy have used steel from this steelworks; you will also find it on the roofs of many houses across Australia.

I work on a programme whose main objective was to speed up the movement of material from one plant to another across the whole operation of the steelworks. Most of these movements were made by train which proved to be slow; a train needed to be put together, moved to the first location, all wagons loaded and finally moved to the other location and unloaded. The programme was to introduce the use of pallet carriers (a special type of truck) into the plant. The pallet carriers used these things called pallets, which resembled tables. The pallet carrier would come along, lower its special suspension, slide underneath the pallet, then raise the suspension again and lift and take away the pallet (after first having dropped an empty pallet). For this to work, it required the introduction of Radio Frequency, or RF, terminals. These were hand held devices which were essentially a portable simple PC using an Intel 386 processor; these were the days before smart phones and tables! (as a note, the 386 processor was eventually superseded by Intel with the 486 which in turn was superseded by the first Pentium processors). So, the programme involved a project to install an RF network across the entire works, projects to upgrade each of the systems in each plant to use these RF terminals and handle these pallets. And finally, the purchase of the pallets and pallet carriers, a system for managing the requesting, allocation and movements of the carriers and the construction of a bridge to join two areas separated by a rail line. I was to manage one of the projects to upgrade one of the systems to use these RF terminals.

I was told that the requirements phase had been completed and approved and would simply move onto design and build, then I was handed the “requirements”. They covered a whole A4 page and a third. It comprised of a table with about 8 rows covering these requirements; each row have between 2-5 bullet points. I know agile people maybe now asking themselves, “so? What’s the problem?” But if this is where you come into the project, this is not much information. It was obvious to me from reading this set of requirements that it wasn’t going to work; I had managed many projects for this plant in the steelworks and understood their business very well. There were more holes in this set of requirements than in a doughnut factory! I then also discovered that the actual end users had had minimal involvement in putting this together and little understanding what this whole thing was about. I insisted on going back and reviewing the requirements and properly engaging the end users; in fact, I demanded it.

We were able to complete successfully the project, although I did spend more than originally planned due to this requirements re-review, but since I got the project variation approved by the client and had his signature on it, not a big deal. All of the other similar projects for other existing plants followed the path dictated only to then require a lot of rework to get it right. The end result, most of the programme’s original budget was spent before critical projects (the purchase of the pallets and pallet carriers, etc) were started; but these projects were where the benefits identified in the business case were to be harvested. The programme budget had made the assumption that the requirements produced were complete and of high quality. So, after a bit of an inquisition (that didn’t worry me, I was born in Spain and therefore know all about inquisitions and I had all of the documentation and approvals to back me up), these final projects were cancelled. While each plant got a bit of an improvement in their operations, this didn’t not justify the overall expenditure. In other words, failure to deliver a project did invalidate the whole programme’s business case.

Now let’s look at a portfolio example. For this I’ll go to one of these “programmes” that were really portfolios that I mentioned in my introduction. So, I was managing this "programme” (which was actually a portfolio which wasn’t that much of an issue for me as I had fulfilled the programme and portfolio manager roles in other organisations) and managing the 5 currently open projects as well. One had been deployed and we were in the warranty period and the other 4 in different phases of their execution. A new project was identified by the client just after I started; once we finished some of the original 5, we started this one as resources became available. We progressed through the initiation, planning and rather long requirements phase. The requirements phase was long because it was quite a complex set of objectives the client wanted to achieve; as they were launching a new product to the market place; they needed to get to an agreed set of features for this new product so that they could begin marketing it; this is very important in financial services. Once the requirements phase was completed, agreed to and approved, we costed it. The estimated costs of proceeding to completion invalidated the whole business case the client had produced and used to obtain approval from their management. The client was left with no other choice and the project was then cancelled. It had no impact on the previous projects or indeed later projects; it just freed funding and resources that could now be allocated to another new project earlier than originally planned.

In Conclusion

Knowing the differences between a programme and a portfolio are extremely important as it impacts how they are managed and the selection of the people to manage them. They need to have the appropriate skillset in order to perform their duties correctly.

This article was written by Michael A. Velez, Castellan Systems’ Managing Director, who has over 40 years’ experience in the IT industry working for several large, multi-national corporations. He has worked as project, programme and portfolio manager.